He Comes in Peace

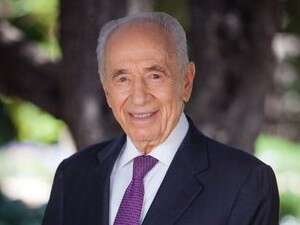

From an uncompromising security proponent to a boundless dreamer, from a kibbutznik and weapons dealer to prime minister and president, Shimon Peres has been present at every major juncture in the history of the State of Israel Maybe that is what makes him, at the age of 89, more popular than ever

From the moment he began to seek public office as a kibbutznik, while still in his teens, Shimon Peres, then Persky, exemplified the spirit of what may come be known as Israel’s “Greatest Generation.” The war in Europe gave special urgency to the Jewish struggle for independence, and the Jewish Yishuv in Palestine, fighting on the side of the British, was an important force in that war. Tapped for leadership by prime minister Ben-Gurion, Peres earned successive appointments in the Defense Ministry where he performed beyond all reasonable expectations. He brokered secret arms deals that provided the Haganah with what it needed to defend the country. After the founding of Israel, through the ingenuity and hutzpah for which his young guard came to be known, he greatly expanded the network of military suppliers and encouraged local arms production for the IDF. His exploits with leaders and arms manufacturers in France, Germany, England and the United States are the stuff of both great diplomatic history and racy undercover fiction.

The renowned scholar Gershom Scholem was once asked how Israel was producing more military men than men of culture; he replied that the Jews were a talented people, and that Jewish talent went where it was needed. This riposte perfectly suits the case of Shimon Peres, who had the cultural inclinations of an intellectual but put his intellect at the service of national defense. Peres is credited for his key role in building the nuclear reactor in Dimona that alone gave Israel deterrent power—at least against enemies with a modicum of rational self-interest. He approved and oversaw the daring raid at Entebbe, and recognized in the ranks of Gush Emunim not the Left’s caricatures of religious fanatics but the kind of pioneering spirit that he had shown in his youth.

Peres made significant contributions to Israel’s security in the critical period of national testing, but there was another side to the man and his influence. In his youth and early manhood—he arrived in Palestine from Poland in 1935 as a child of 12—he wanted very much to be the exemplary pioneer, and he embraced the collectivist ethos and the agricultural ideal. Yet he never shed the Polish accent, the traces of a religious upbringing or the affinity for European culture that would forever distinguish him from the mythic type of the “sabra.” It was particularly held against him that he did not fight and risk his life in the War of Independence—a failure that was later exploited by his political rivals. That he shouldered defense responsibilities as a member of government ensured that attention would continue to be paid to this lapse (which he regretted), despite contributions to Israel’s military efforts that were certainly greater than any he might have made in uniform.

Though Peres was much more the political insider than British-accented Abba Eban, he was similarly suspected of “foreignness” for the urbanity that made both men so successful in their dealings abroad. Eban was the proud and visible spokesman for Israel; Peres developed private and often secret channels with leaders, many of whom did not want their association known.

Peres had certain habits of mind and spirit that his friend, the novelist Amos Oz, has attributed to an “unquenchable thirst for love”; he himself has attributed them to an unquenchable faith in a better future. It was said that, so convinced was he of his own integrity and unimpeachable intentions, he often pursued his plans without proper consultation and without the kind of “worst-case” preemptive thinking that informs judgment at its best. Not inclined to address everyday issues like immigration and absorption, education, communication or finance, he aspired to engineer a peaceful solution to an Arab war against Israel by ignoring its roots, which went back to the Jewish state’s very existence.

As long as he was a member of the party in power—Mapai and its successor Labor coalition—Peres’s schemes (sometimes called harebrained) were held in check by leaders, rivals and advisors in his own ranks. This changed dramatically with the Likud victory in 1977 and the rise of a conservative-tending opposition to Labor’s longstanding hegemony. Rather than taking this political development as one of democracy’s inevitable shifts of power, or of the Israeli electorate’s preference for a stronger foreign policy (and a freer economy), Peres was persuaded that he had to save Israel from the Likud. Like many on the Left, he fantasized that the West Bank of the Jordan, taken and held by Israel in consequence of aggressive Arab belligerence, was the cause of Arab belligerence, and that peace could be achieved

through territorial concession. He began to conduct his own foreign policy against the wishes and without the knowledge of the elected government.

There were several drawbacks to this pursuit. Even among a people never known for its political wisdom, Peres was a poor political thinker. This became ever clearer with each new booklength effort at displaying his gift for political insight. The Imaginary Voyage (1998) takes up the motif of Herzl’s Old-New Land by giving the founder of political Zionism a tour of the country he had once only imagined. At the end of the tour, Herzl reflects, “If you will it, it is no dream,” confirming that his vision of 1902 had become actuality in present-day Israel. But to this the Peres narrator replies: “Today, this dream has another name, the most beautiful in the Hebrew language—shalom, peace.” The implication—that Peres’s political vision is the latter-day incarnation of Herzl’s—could not be more mistaken. In fact, the two rest on opposite foundations—Herzl’s primarily on what could be done by dint of Jewish effort and ingenuity, Peres’s on wishful thinking about Arab priorities. Under the banner of Hatikvah, Peres confused the hope placed by Jews in their own capacities with a hope invested in belligerents bent on revanchist or eliminationist ends.

A somewhat earlier exercise of the imagination was Peres’s 1993 volume The New Middle East, which a reviewer called a failure of imagination: a failure, that is, to imagine Arabs as they really were. Indeed, all of Peres’s writings in this mode were based on the same set of projected assumptions, unchangeable no matter how often they were falsified by experience. By this time, however, what might have remained airy intellectual exercises had become dangerous as their author began conducting his own foreign policy based on these chimerical premises.

By his own account and that of associates he recruited to the task, Peres employed the same clandestine strategies he had once used to evade Israel’s enemies in furtherance of a “peace process” that explicitly contravened the three-pronged slogan on which Yitzhak Rabin had been elected in 1992—“no negotiations with the PLO” being the first prong. The stealthy talks Peres and his team conducted with the Palestine Liberation Organization issued in one of the great cons in political history—with Israel as the dupe. Trusting an organization whose primary goal was the extermination of Israel to become its partner in coexistence, the Peres teamaccepted a handshake from Yasser Arafat as if the PLO chieftain were an Antwerp diamond dealer.

Israel has been punished for this political folly. Whatever credit—or Nobel Prize mementos—its leaders may have received at the time for ostensibly hastening peace via the Oslo “process” now redounds to its discredit for having willingly birthed a terrorist haven on its very doorstep. By 2000, the Knesset seemed to render a final verdict on Peres’s political career when Moshe Katsav edged him out for the presidency by a vote of 63 to 57. But the hunger for peace, or the illusion thereof, will never abate in democracies. Katsav’s fall in 2007 under a cloud of scandal turned the wheel of fortune, and Peres was then elected to a seven-year term.

This is a felicitous end to an uneven political career. Peres the benign elder statesman is in the right place at the right time, welcoming foreign guests with the kind of reassurances they hunger for. His lack of overt ostentation, avid interest in the humanities and sciences, and faith in the country he helped to build: All these help to bring a sense of restorative wholesomeness to the presidency.

Peres’s influence radiates from knowing instinctively what American pollster Frank Luntz advises his clients: “The speaker that is perceived as being most for PEACE will win the debate.” Having laid claim to this term, Peres attracts grateful American donors, international diplomats, and those eager to believe that the Arab Spring is in blossom. As for his fellow Israelis, they in their maturity have shown that they can tolerate prophetic fantasies in their religious and ceremonial leaders—just not in their functioning politicians.